- Fragile Planet Offers a Nighttime Wildlife Experience

- Falcons Soccer Off & Running

- Cameron County Receives Funds to Improve Two Parks

- Falcons Complete First Half of 32-6A

- School District to Help out Victims of California Wildfires

- Sand Castle Days Continued Despite Unexpected Weather

- Ready for District

- Discussion of Garbage Dumpster Rates, Agreements Between State & City on Highway Regulations, and More

- 31st Annual Shrimp Cook-Off is Right Around the Corner

- LFHS Cross Country

UTRGV Faculty and Students at Forefront of Zika Research

- Updated: August 3, 2018

Dionn Carlo Silva, a UTRGV biology graduate student, is seen here in UTRGV assistant professor of biology Dr. John Thomas’s lab on the UTRGV Edinburg Campus, working on characterizing the effects of Zika and Dengue virus replication in opossum colonies. UTRGV Photo by Victoria Brito

by Victoria Brito

RIO GRANDE VALLEY, TEXAS – In the aftermath of recent flooding in South Texas, the Rio Grande Valley is facing major public health concerns with a growing mosquito population, which can lead to a potential outbreak of certain vector-borne diseases like the West Nile and Zika viruses.

To combat these pests, Dr. Christopher Vitek, UTRGV associate professor of biology, and Dr. John Thomas, UTRGV assistant professor of biology, and a group of dedicated UTRGV students have been working on research to address the Zika virus, not only in the Valley but across the United States. Their research is part of the work by the Western Gulf Center for Excellence for Vector-Borne Diseases, a multi-institutional consortium funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To showcase the inner workings of the university’s facility and research, UTRGV on July 17 opened up its lab in the new Science Building on the Edinburg Campus for a tour, where visitors were able to observe students and professors at work.

One visitor included state Rep. R.D. “Bobby” Guerra, who was involved in the passing of House Bill 3576, which provides more resources to aid the Texas Department of State Health Services in tracking, monitoring and preventing the spread of the Zika virus.

“I am proud of the great work being done at UTRGV in response to this major threat to the public health of our community,” Guerra said.

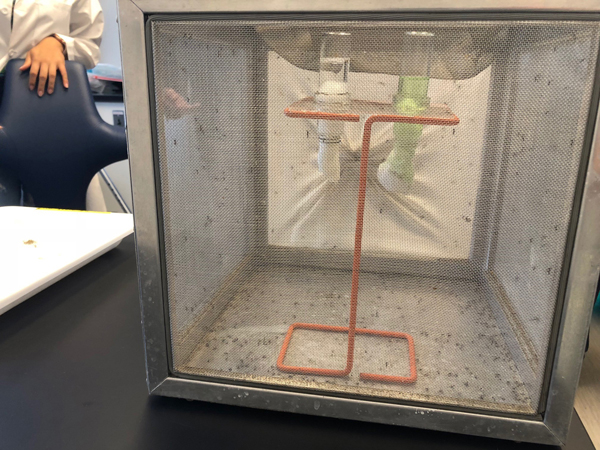

Live mosquitoes are seen here in a rearing facility at a Zika research laboratory on UTRGV’s Edinburg Campus, part of the Western Gulf Center for Excellence for Vector-Borne Diseases, a multi-institutional consortium funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. UTRGV Photo by Victoria Brito

ZOOMING IN ON ZIKA

During the tour, visitors saw how mosquitoes were tested and identified and how information was gathered. They also got to see the layout of the lab, which is divided into two sectors – entomology and pathology.

The west wing of the lab, led by Vitek and a team of student researchers, is dedicated to entomology, including counting and identifying the species of mosquitoes.

“This is where we work with the mosquito side of things. I always say I work on the dirty side of biology. Either my students or I are out in the field collecting samples. And we work with counting mosquitoes and identifying them,” Vitek said.

Heather Hernandez, from Donna, a graduate student who serves as the lab manager of Vitek’s side of the lab, worked on sampling and testing insecticide resistance to certain chemicals, mainly permethrin and deltamethrin, on wild-caught mosquitoes from Harlingen.

Vitek said there are certain threshold levels in which mosquito populations become immune to certain chemicals, so testing is crucial. The goal is to kill the mosquitoes within 30 minutes to one hour of exposure to the pesticide.

“Permethrin has been working after 10 minutes,” Hernandez told the tour group.

Once results have been collected, reports are compiled and sent to the state and the CDC, Vitek said.

In Vitek’s lab, students also work on hatching mosquito eggs collected from across the Valley. The mosquitoes live in a rearing facility and are used for studying.

“We try to keep our mosquitoes away from the lab as much as possible, to avoid potential escapes or someone getting bitten,” Vitek said.

In the east wing, Thomas works on the viral aspects of Zika. His students primarily do molecular work, including virus diagnostics in animal models, and ways to diagnose and test for the virus.

Thomas’ students extract viral RNA (ribonucleic acid – a molecule fundamental in biological coding, regulation, etc.) because the Zika virus is an RNA virus, he said.

“We have to extract all the RNA from a cell or animal tissue and separate the Zika RNA and the non-Zika RNA to look at the virus itself,” Thomas said.

“We will grow a monolayer of cells and infect the cells with the virus, and if there is virus, the virus will grow in a pinpointed location. This is actually how we count the viruses,” he said.

Juan Garcia, a biology graduate student from Edinburg, serves as Thomas’ lab manager and is in charge of collecting mosquito samples from municipalities across the Valley.

“It takes a lot of patience,” Garcia said.

Dr. Christopher Vitek (at left), UTRGV associate professor of biology, and state Rep. R. D. “Bobby” Guerra (center), spoke this week in the Zika research lab on the Edinburg Campus, as biology graduate student and lab manager Heather Hernandez performed tests on pesticide effectiveness. Guerra and other guests toured the facility and got updates on important research UTRGV is conducting on Zika and other vector-borne diseases. UTRGV Photo by Victoria Brito

DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE ON RESEARCH

In addition to the lab in Edinburg, Thomas said, his research utilizes the Brazilian opossum colony housed on the Brownsville Campus.

“We know that Zika can do all of these deleterious things to the human fetus, and we know that when pregnant mothers are exposed to Zika, there can be severe abnormalities with the children,” Thomas said. “One of the things we are looking at is, how does that happen?”

One of the most prevalent observations is the overall growth of opossums infected with the Zika virus, particularly in the sex organs, which have been halted in growth and development. When the Brazilian outbreak of 2015 occurred, microcephaly was the condition most notably associated with Zika births.

“During the outbreak in Brazil, there were about 4,000 children born with microcephaly. We have been so focused on looking at the brain part of it, no one has thought to look at what will happen to these children when they are ages 12 and older,” Thomas said. “Will they have their sex organs? Will they be sterile? We are just now starting to look at the interactions of the Zika virus and the sex organs.”

Discovery of that kind will take years of research, he said.

One Comment